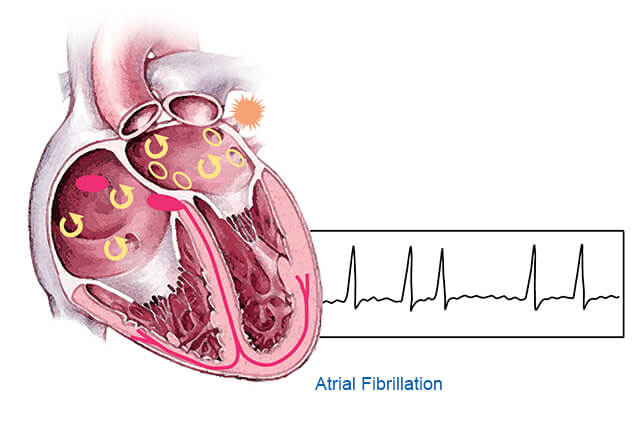

AFib can raise your odds of stroke, heart failure and dementia. It can also make breathing difficult.

A health care provider will do a physical exam and ask you about your symptoms. They might use an EKG to check your heart rhythm.

AFib can come and go (paroxysmal AFib) or you may have it constantly (chronic AFib). Your doctor will decide on the best treatment based on how long your episodes last.

Symptoms

During an episode of AFib, your heart may quiver or beat irregularly and fast. This can cause a feeling of discomfort in your chest or throat. You might also feel that your heart is skipping a beat, fluttering or racing.

These episodes might only last a few minutes or hours and don’t need treatment, especially if they occur infrequently. But they can make you tired or short of breath, even when you’re doing only mild activity. They can also increase your chance of stroke.

Some people have no symptoms and don’t know they have AF until it is detected on a routine test. If you have symptoms, keep track of them so that you can report them to your doctor. Your doctor might order diagnostic tests, including a holter monitor or a Zio patch that records your heart rhythm over 24 to 48 hours, blood work and an echocardiogram (which uses a wand-like device to create a video of your heart working). The doctor can use heat ("radiofrequency ablation") or cold ("cryoablation") energy to destroy the areas of your heart sending abnormal electrical signals.

Risk factors

Afib increases your risk of stroke, blood clots, heart failure and other serious health problems. But you can take steps to lower your risk. These include taking blood-thinning medications, slowing your resting heart rate and having a procedure called cardioversion or catheter ablation to restore a normal rhythm.

A doctor can diagnose Afib by doing an electrocardiogram (ECG) in your doctor's office in a matter of minutes. You may also wear a portable monitor called a Holter or event recorder for 24 to 48 hours to get a more complete picture of your heart rhythm.

Certain factors put you at higher risk of developing Afib, such as a family history of the condition, age over 65, chronic lung disease, heart valve disease, thyroid problems and high blood pressure. You can reduce your risk by exercising regularly, maintaining a healthy weight, not smoking and drinking alcohol only in moderation. Afib disproportionately strikes women and minorities, who are less likely to seek medical care for symptoms.

Tests

If a person thinks they have A-fib, their doctor will listen to their heartbeat with a stethoscope and ask about symptoms and risk factors. They'll also do a physical exam. Then they may order blood tests and other tests to confirm the diagnosis.

One important test is an electrocardiogram (ECG, or EKG). During this test, special stickers called electrodes are placed on the chest, arms, and legs to pick up signals that show up on the monitor as wave patterns. The test is quick and painless.

Other tests include an echocardiogram, which uses sound waves to create a picture of your heart. This can help doctors see if there are blood clots in the heart. They might also use a device called a cardiac event recorder, which can be worn for up to two weeks and records the heart rhythm when activated. The doctor can then play back the recordings to look for signs of arrhythmia.

Treatment

The good news is that treatment can reduce your risk for serious complications from AFib. It may include medications, procedures such as electrical cardioversion or ablation, and lifestyle changes.

Medications can help reset your heart rhythm and prevent clots, slow your heart rate, and control symptoms. If underlying problems like high blood pressure, cholesterol, or an overactive thyroid contributed to your AFib, treating those conditions can also help.

A common complication of AFib is stroke, because blood can pool in your atria and clots can travel to the brain. Your doctor may prescribe blood-thinning medicine to reduce your risk of a stroke.

If your episodes of AFib are paroxysmal (they come and go), you might need medication or an electrical procedure called cardioversion to get your heart back into a normal rhythm. If your episodes are persistent, you might need a more invasive procedure called catheter ablation to destroy - through tiny burns - the chaotic electrical impulses in your heart that cause the irregular rhythm. You might also need to have a pacemaker implanted.